Texte lu devant le jury du Prix Marcel Duchamp 2025

(Scroll down for English)

C’est un honneur pour moi de vous présenter le travail de Xie Lei aujourd’hui.

C’est un honneur et une mission importante.

Pour celles et ceux qui ont rencontré l’artiste, vous avez probablement remarqué

sa présence,

son respect,

son silence,

Xie Lei est un taiseux.

Et comme tous les taiseux, c’est un adorateur du langage.

Un mot ne vient jamais par hasard.

Il y a quelque chose de fort dans son lien au langage.

Dans le pouvoir qu’il donne à chaque mot.

Dans le pouvoir qu’il donne à chaque titre

Comme ici, avec Fall

C’est un premier texte extérieur.

La partie visible du silence. Je me suis donc posé la question :

Quels textes intérieurs animent cet homme ?

Quels sont les enfants du silence, dans l’opération de sa peinture ?

Je vous propose de commencer avec une série dans laquelle vous vous êtes immergé.

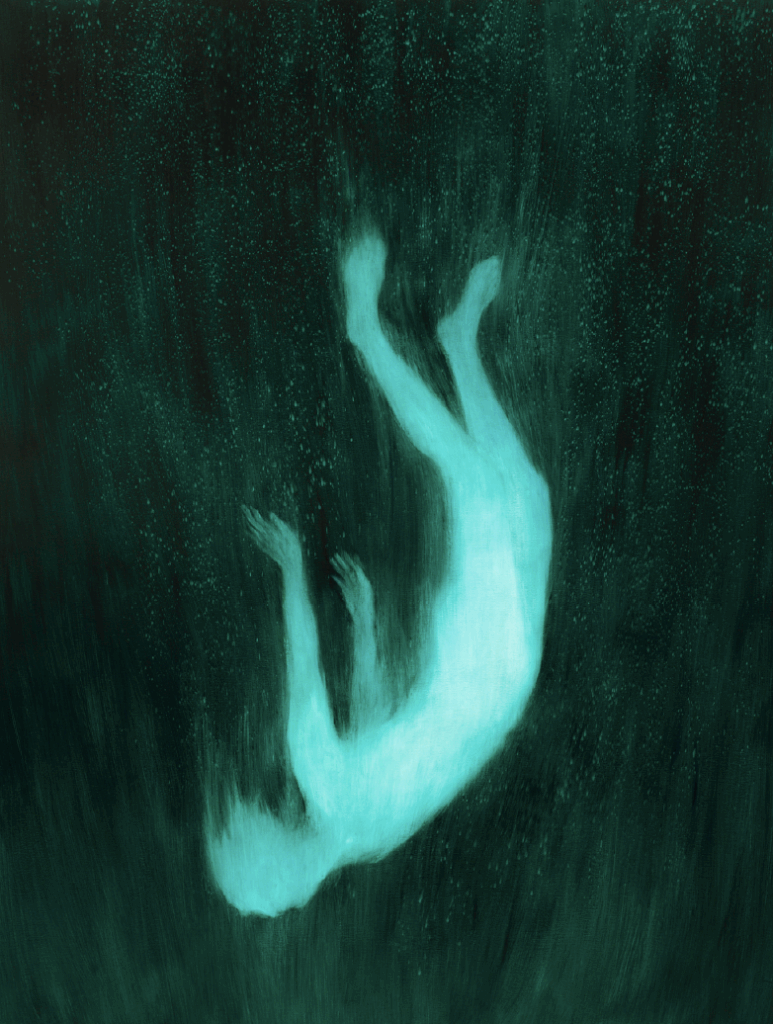

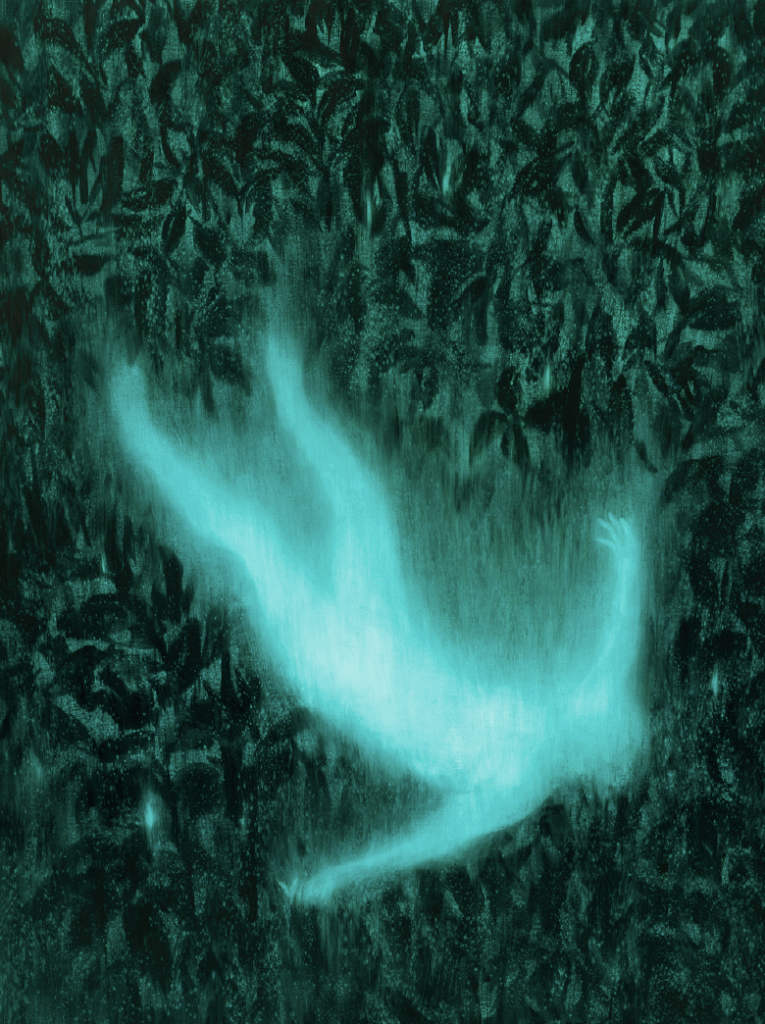

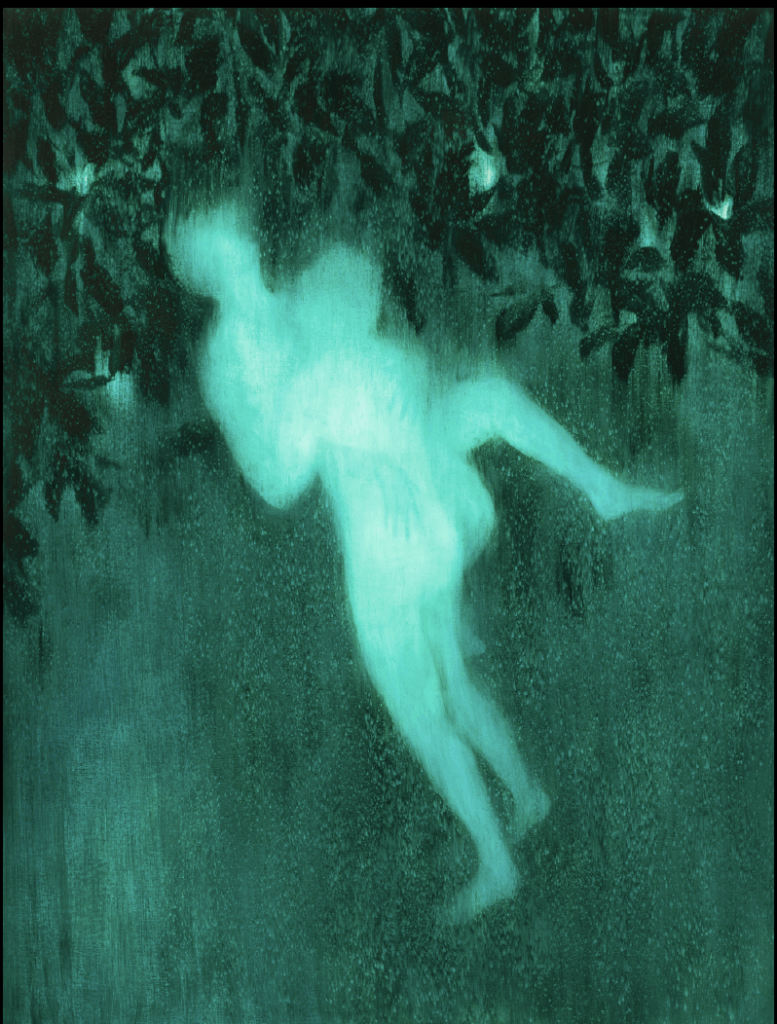

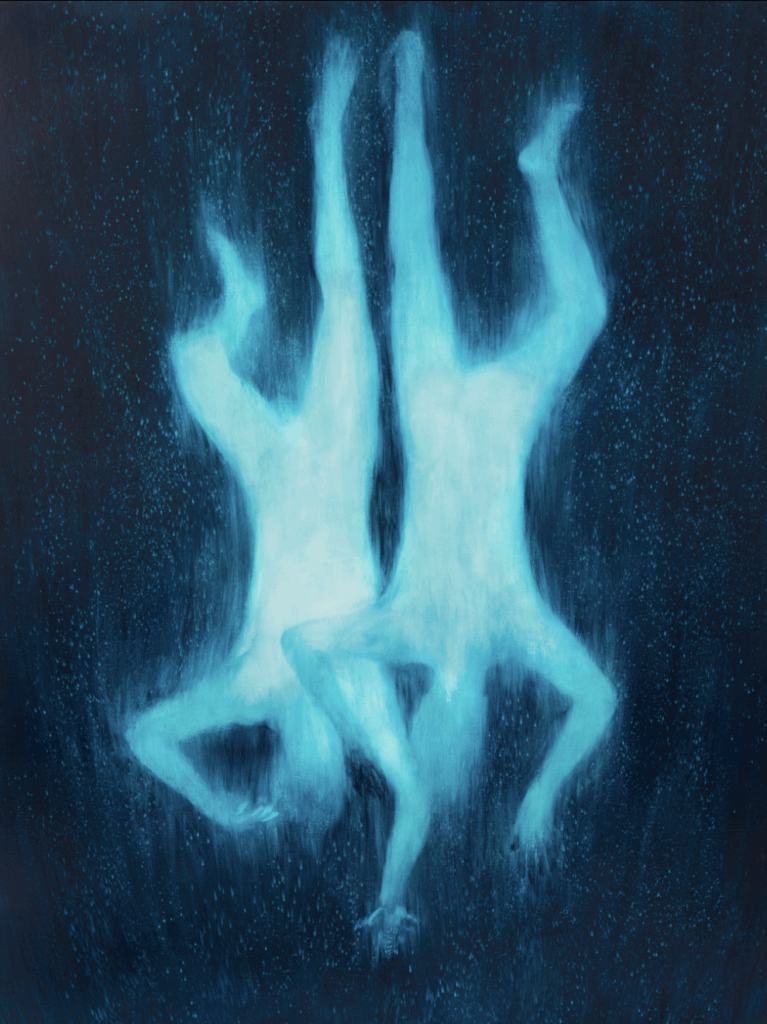

Fall est une installation pensée pour les espaces du Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris dans le cadre du Prix Marcel Duchamp.

Sept œuvres de grands formats, 270 x 205 cm, taillées sur mesure pour les espaces. L’œuvre de Xie Lei se découvre dans son envergure panoramique et son sens de l’installation. Un environnement d’écume vert-bleu et de touches de blanc,

un camaïeu,

d’où jaillissent des corps, un corps, deux en train de tomber. Autrement dit, des états de chute, que Xie Lei souhaitait réaliser depuis longtemps.

On pourrait bien entendu penser aux chorégraphies de la peinture murale La Danse de Matisse présentée à proximité.

Les corps blancs en mouvement de Matisse rentrent en résonance avec les corps d’opaline de Xie Lei

Mais ici, les corps sont inversés.

Ils plongent, tête, nuque, échines tournées vers le bas.

Que dire de la Chute ?

Que dire de Fall ?

Il me semble qu’il y a plusieurs raisons pour lesquelles un peintre comme Xie Lei se confronte à ce motif.

La chute abonde dans de nombreuses mythologies (occidentales, orientales, chinoises) il est un défi pictural majeur.

Mais surtout, la chute se loge en chacun, chacune de nous.

Gaston Bachelard nous rappelle qu’elle renvoie à une peur primitive, celle liée à nos ancêtres arboricoles qui auraient intégré en eux la peur de tomber.

En cela, elle serait universelle, intime, collective.

Elle est si ancrée…qu’elle se mue, se niche dans d’autres imaginaires.

La chute pure, ce jet de l’homme à la verticale est rare – même si, Xie Lei a souhaité donner un visage à cet état corporel extrême, comme ici avec Fall I.

La chute est la sœur de la condensation :

Elle regroupe d’autres états : la lévitation, l’inclinaison, l’élévation, la suspension, le plongeon.

Elle regroupe d’autres imaginaires : une étreinte, un drame, un ébranlement amoureux.

Elle s’éclipse derrière autre chose.

Et, L’histoire de l’art nous l’a montré : Yves Klein avec « Le saut dans le vide » nous donne un saut sans chute.

Il habite le vide, sans tomber, défiant la gravité.

Face à cette multitude de visages, Xie Lei, s’est réellement posé la question.

Comment représenter ces chutes aux multiples significations ?

En travaillant ces nappes chromatiques, ces camaïeu vert-bleu, Xie Lei a trouvé le pendant pictural à la polysémie de cet état :

Un environnement quasi monochromatique qui tend vers une sensation trouble, plurielle, apaisante :

Obtenu par l’application de plusieurs couleurs qui se glissent dans ces fonds mobiles.

Xie Lei dépose des couches très fines, liquides, transparentes de peinture à l’huile, sur un gesso qui agit comme une seconde peau.

Un travail de superposition qui n’accuse jamais l’effet de trop de matière.

Ses pinceaux – ample, doux, en poil de cochon – sont imprégnés de la juste quantité de peinture à l’huile : ils sont comme ses mots.

Ce qui procure cette palette restreinte, oui, mais profonde telle

une sensation d’eau profonde ou de nuit nuit lorsque par endroit, des zones se font plus saturées, plus mystérieuses :

Le vert y devient profond. Profond comme un noir.

Intranquille comme un noir – et pourtant le noir, dans sa palette est absent.

Une sensation d’eau profonde qui ouvre sur d’autres puissances matérielles :

Quand le sentiment d’eau rencontre le vent (la vitesse)

Quand le sentiment d’eau rencontre le feu – cette sympathie thermique, capable, selon Bachelard, d’unir le bien et le mal.

Quand le sentiment d’eau touche la terre, éveillant notre sympathie matérielle pour le végétal.

Les arbres, lieu de nos ancêtres. Des feuilles, de magnolia

Quand le sentiment d’eau se mêle à l’air :

Vous avez peut-être remarqué ce perlage qui encercle les corps, qui se meut dans les fonds.

Un crépitement de lumière, un perlage de bulle obtenu par le retrait de la matière.

Lorsque le tableau arrive à l’étape finale, Xie Lei prend un pinceau plus gros pour l’imbiber de térébenthine, et le projeter à quelques endroits du tableau.

Ce n’est pas une dépose, c’est un projeté :

un projeté de non-matière, qui sera, ensuite, délicatement retiré,

avec un pinceau aux poils doux, un papier, ou ses propres mains.

Car ici, il s’agit d’extraire, plus que d’ajouter.

Et de toutes les touches qui constituent le tableau, ce sont peut-être les plus discrètes.

Celles qui confèrent cette impression d’étoiles… plongées dans un sentiment d’eau,

elles participent à cette texture de l’imaginaire et profondeur de l’étrange qui habite les toiles de Xie Lei.

Jusqu’où puis-je/pouvons-nous traquer l’étrangeté et l’onirisme, comme catégories esthétiques – mais pas que – dans la genèse de son œuvre :

Chez cet artiste, formé à la peinture depuis ses six ans en Chine, l’exploration d’un onirisme en couleurs ne s’est pas révélée d’un seul coup lors de son arrivée en Europe.

Elle mûrit en lui depuis longtemps.

Pour cet artiste qui a suivi une formation académique nourrie à la fois de la tradition académique européenne et chinoise, l’étrange est une donnée picturale et une composante de la vie

Déjà enfant, à Huainan :

Il observe les feux follets, fruit d’une réaction chimique, qui émanent des tombes du cimetière voisin,

Il observe la profondeur de l’eau qui lui fournit ses premières peurs et ses premières couleurs.

Cela se mêle dans son apprentissage de la montagne et d’eau (shan shui), une peinture de paysage en noir et blanc, qui contient du vert, du bleu, du silence.

Un geste juste.

Se consolide lors de ses années aux Beaux-Arts de Paris, qu’il intègre en 2006, lors de son arrivée en France, et avec la rédaction de sa thèse de doctorat, soutenue en 2016, sur la poétique de l’étrange.

Se révèle, telle une épiphanie lorsqu’il arpente les musées de Düsseldorf, de New York ou de Madrid pour traquer la force polychromique des œuvres de Zurbarán et Velázquez – dont les reproductions ne le quittaient jamais lorsqu’il était étudiant en Chine – Celles d’Alonso Cano et Luis de Morales, qu’il a découverts lors de sa résidence à la Villa Velázquez, l’Académie de France à Madrid.

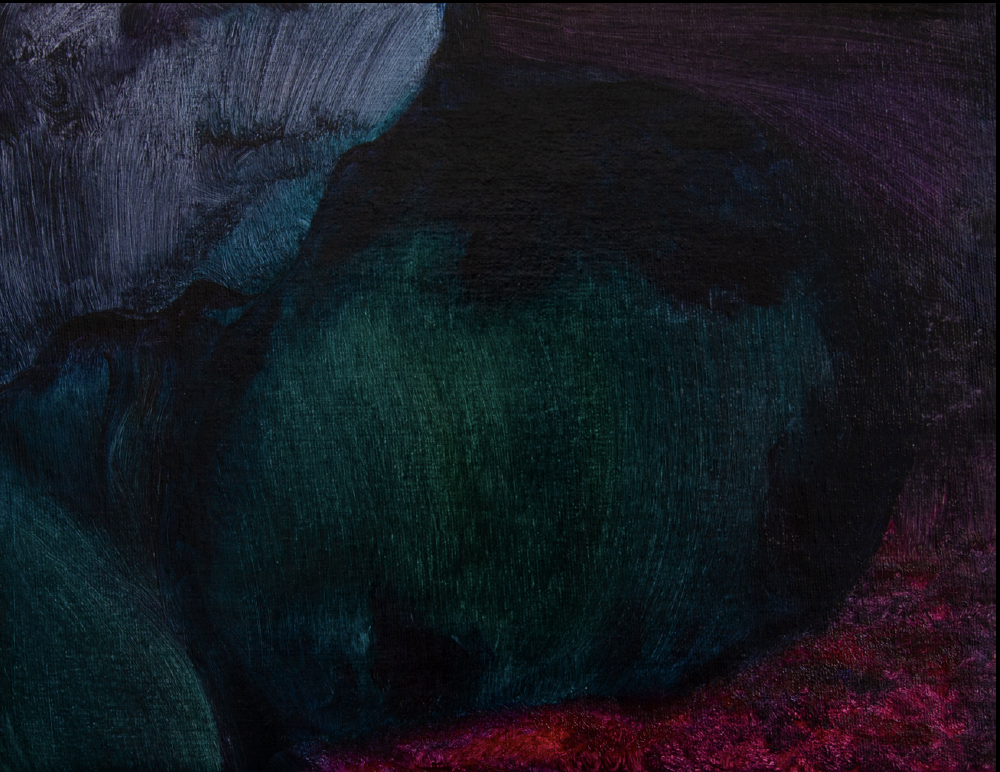

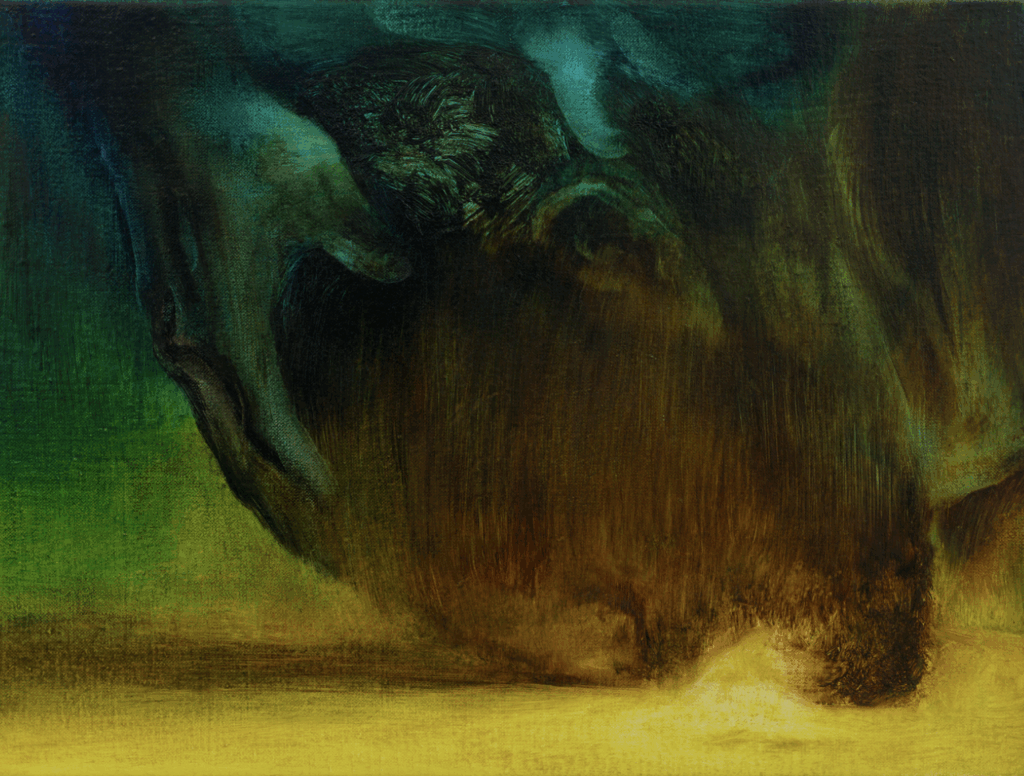

Il y découvre et retient une forme de « ténébrisme en couleur » qui a trouvé son paroxysme dans Slumbers.

Une série qui traite d’un état en cours.

Xie Lei cherche à dépeindre le temps d’une action en cours.

Une action suspendue dont la finalité reste ouverte.

Bien qu’il peigne depuis plus de trente ans, le cinéma peut apporter un point de départ structurant.

Vous l’entendrez dire qu’il « essaie de faire des films avec la peinture ».

Et de fait, ce qu’il cherche, depuis près de vingt ans, c’est aussi créer un effet cinématographique dans son art :

Il y a plus de 20 ans en effet le choix du cinéma comme carrière s’est posé à lui.

Il y a plus de 20 ans le cinéma est rentré dans sa vie.

Jean Genet avec Un Chant d’Amour qu’il découvre dans un cyber café à Pékin lorsqu’il est encore jeune homme.

Pier Paolo Pasolini et plus particulièrement Salò ou les 120 Journées de Sodome qu’il admire pour sa méthodologie quasi-liturgique, détachée, et la prégnance d’une esthétique issue de la peinture classique.

Des films silencieux, visuels aussi comme ceux de Béla Tarr.

Des films en noir et blanc pour un artiste qui a pourtant récusé ces couleurs.

Il y a Printemps dans une petite ville de Fei Mu.

J’aimerais rajouter Apichatpong Weerasethakul pour son temps distendu, celui du sommeil peut-être qui s’ouvre à d’autres présences…spectrales, végétales…

Et si, le cinéma est le lieu du temps, de l’action et de la narration Xie Lei insiste :

il ne cherche pas à raconter des récits.

Ce qu’il propose c’est une situation suspendue.

Un état figé dans sa lente transformation.

Comme ici, avec Slumbers, où il met en scène des actions presque invisibles.

Des transitions minuscules :

Lorsque le souffle devient râle Lorsque le plaisir se fond en sommeil.

Slumbers donne à voir un homme en train de « dormir, en train de mourir, en train de jouir »

Et pour cause, Xie Lie emploie un geste ample et vif pour créer un fondu troublant. Des couches, de peinture à l’huile, qui donne cette matière dense, impétueuse d’où nait une forme incertaine.

Le visage, indistinct se meut dans le fond.

Il est visage comme il est pénombre : pénombre colorée.

Des teintes chaudes et terrestres, brunes, ocres.

Des teintes froides, principalement des bleus profonds.

Et toujours ce vert, ce bleu qui frôle le noir.

Un ténébrisme au service de la couleur.

Xie Lei ne peint pas une action figée mais un « en train de » à la manière du -ing en anglais.

Pourtant, le titre n’est pas Sleeping — qui aurait fait trop de bruit. Trop bavard, narratif.

Slumbers suggère un silence intérieur, une vibration d’un râle :

Il a pour texte intérieur la profondeur d’une expérience humaine fondamentale.

Dont l’exercice même de trouver « le sens pour moi », autrement dit le sens propre, nous demandent d’être des observateurs discrets, des témoins furtifs.

Xie Lei traite le tableau comme un cadrage.

On regarde par le trou d’une serrure : 27 x 35 et 33 x 41 ; 30 x 40 cm.

Ce sont les formats attribués à Slumbers qui lui confèrent une intensité particulière, s’ouvrant ….sur la polychromie d’un monde intérieur.

Au-delà du temps, au-delà du principe du cadrage, Xie Lie intègre la lumière digitale dans le secret de fabrication de son œuvre.

Le cinéma et la peinture, en sœurs alliés, se mettent au service d’une œuvre qui appelle à son propre dépassement.

Pour nous porter, doucement, vers l’idée, d’une boite lumineuse.

Xie Lei fabrique cette lumière.

Il la construit pour qu’elle illumine la peinture :

Comme une incandescence.

Une capture thermique Comme un halo spectral.

Qui ne résulte pas d’un ajout de blanc.

Le blanc, dans sa palette n’existe plus depuis quelques années.

Il est comme le noir.

Pourtant ce blanc est présent.

Il ne le peint pas.

Il le fait surgir.

Il le fait surgir, par transparence en révélant la blancheur du gesso, en révélant sa lumière :

En frottant, à l’aide d’un tissu, d’un pinceau, parfois de ses mains nues, les couches supérieures qui constituent le camaïeu.

De fait, la figure est une quasi réserve.

Une trouée.

Elle n’est pas peinte, elle est excavée.

Et ce presque blanc ici n’est pas une couleur, mais une absence modelée.

Qui crépite un peu plus à quelques endroits.

« Laisser le blanc » en chinois, liú bái, désigne l’action de laisser un espace vide, un vide intentionnel.

J’y vois encore ce silence.

Pour Xie Lei, ce blanc est une présence, le bruitage dans un film.

C’est un processus similaire à celui du perlage.

Excaver la matière – elle qui est lisse comme une peau.

Mais surtout :

Lisse comme une image.

Lisse comme un écran.

Xie Lei chérie la peinture à l’huile pour ce qu’elle offre comme effet de caresse.

Il peut la toucher, puisqu’elle est à la fois grasse, lisse et effaçable.

Elle est comme une crème, dit-il.

Il me semble qu’il y là une résonance avec sa façon de peindre et la caresse qui efface les sujets :

Dans Fall V, une main apparaît en transparence sur le corps d’une figure.

Elle touche sans saisir. C’est une caresse spectrale, un tact de spectre.

En cela, la peinture est une apparition.

Et l’image est à envisager dans un système de montage qui relève, là encore, du cinéma comme lieu de la hantise

Si l’on se tient à cette lecture, pouvons encore parler de série pour le travail de Xie Lei?

Avec un commencement et une fin ?

Son travail repose sur le débordement, l’irruption, la réapparition.

Il se construit sur des motifs récurrents, des leitmotivs réactivés d’une toile à l’autre.

Le tableau n’était jamais tout à fait clos, mais toujours ouvert au devenir et également au passé.

Comme ici, à la BNF, dans l’exposition Apocalypse, où l’œuvre de Xie Lie est reliée à l’Histoire dans un fondu enchaîné qui rapproche une époque à une autre, une œuvre à une autre :

Dès lors, Xie Lei propose des séquences ouvertes, informes.

Fall, en ce sens, n’est pas seulement un moment d’exposition :

C’est un leitmotiv, une figure obsessionnelle qui ressurgira dans d’autres œuvres à venir.

Et si l’on prolonge cette interprétation, ces peintures pourraient être vues comme des représentations panoramiques des états de l’être humain – un être pris à la fois dans le sommeil et dans la chute.

Peut-être même s’agit-il de deux figures de l’homme :

L’un vertical, l’autre horizontal.

L’un qui dort, l’un qui chute, même si la chute, agit déjà, peut-être, dans le sommeil, dans Slumbers puisque

« le sommeil est l’endroit de toutes les chutes, il les rassemble » (Jean Luc Nancy)

deux figures, donc, qui pourraient bien n’en former qu’une seule.

Deux états d’un même corps.

Où se tient Xie Lei dans ses toiles ?

Et où choisit-il de ne pas apparaître ?

Xie Lei ne s’oublie pas comme corps dans la peinture.

Ce gabarit corporel pourrait être le sien — un corps à l’échelle réelle Mais la toile n’est pas un autoportrait.

Elle serait plutôt le lieu d’un soi mouvant, fuyant l’assignation identitaire.

Ce que José Esteban Muñoz appelle la désidentification : une tactique fluide, entre retrait et apparition, où l’identité devient fugace, insaisissable.

La présence de Xie Lei dans sa peinture s’affirme par l’absence, par sa fugacité dans les traits qu’il estompe, dans ceux qu’il gomme de sa propre main, jusqu’à laisser, çà et là, l’empreinte discrète de ses doigts.

En effaçant, il s’inscrit.

Et peut-être faut-il lire ces figures — endormies, déchues, flottantes — à la lumière de cette notion.

Leurs contours diffus résonnent avec la dilution de l’identité ; leur flottement dit une forme de décentrement du moi.

Où l’artiste négocie — silencieusement — avec ce qu’il est :

Peintre et homme,

expatrié.

Ces traits, il ne souhaite les mettre au grand jour.

Il préfère les diluer dans l’espace généreux que permet la désidentification.

Il les négocie en interne : son texte intérieur.

Il chorégraphie une absence à soi qui ouvre la voie aux autres : le spectateur peut s’identifier à ces corps sans nom, anonymes, sans distinction nette entre féminin et masculin, même si parfois le genre masculin est suggéré dans quelques peinture de Fall ou Slumbers.

Mais globalement, elles offrent l’image d’un corps universel et poreux, dans lequel chacun peut projeter sa propre vulnérabilité.

On peut encore s’identifier dans ces zones de blanc, qui ne sont jamais vides : elles crépitent de sous-entendus.

Ou encore dans les ombres, celles qui, pour Annie Lebrun, nous font grandir.

Ces ombres en couleurs qui deviennent le lieu de l’énigme et d’une insurrection lyrique, tout en murmure.

Ce qu’il souhaite rendre possible, c’est la reconnaissance d’un fond commun, une mémoire partagée.

Xie Lei c’est un grand fédérateur

Les signaux du réel peuvent émerger.

C’est un rapport légèrement plus direct avec le réel.

Comme ici, avec Absorb qui est traversé d’images fortes que l’actualité nous renvoient du monde.

Ou ici, dans Au-delà, nourrie d’une image dont je préfère taire le nom.

Ce serait trahir le silence de son œuvre que de vouloir en faire un grand discours.

Xie Lei ne sur-affirme pas, mais nous offre la possibilité de nous confronter à un panorama intérieur.

Plonger dans le sentiment d’eau, dans la chute, dans le sommeil, dans les couleurs de ses fonds mobiles.

Et la question que je me pose désormais :

La perspective panoramique de ses installations, au fond, ne viendrait-elle pas nourrir cette ambition ?

Celle de nous inviter à plonger en nous-même : Un romantisme de la désidentification.

Que va faire ce peintre, lui qui, à 15 ans, a quitté sa province de l’Anhui pour aller étudier à Pékin – au lycée rattaché à l’Académie centrale des beaux-arts ? Lui qui a ensuite traversé le monde, porté par une exigence sans nom, pour poursuivre sa formation aux Beaux-Arts de Paris, ville où il vit depuis 2006 (bientôt 20 ans) – et où il travaille, précisément dans son atelier se trouve à Thiais, en périphérie, près d’un jardin dont il extrait certains de ses motifs végétaux.Ces feuilles de magnolia

Que va faire cet artiste, qui ne s’est pas contenté de la peinture comme pratique, mais l’a pensée, formulée, interrogée.

Car il se sent doté de cette responsabilité.

Il a été le tout premier artiste à soutenir un doctorat SACRe, au sein de l’École des Beaux-Arts et de l’École normale supérieure.

Que va faire ce peintre lui qui a rêvé la France depuis la Chine, puis rêvé l’Italie et l’Espagne depuis la France ?

Qui a connu l’Italie avec une résidence à la villa Médicis en 2024.

Qui va voir Velázquez à New York, il va voir le Titien à Vienne, il va voir Zurbarán à Düsseldorf

Qui a eu une révélation en allant à Madrid lors de sa résidence à la Casa Velasquez Académie de France à Madrid en 2020 lors d’un moment « hors du temps » ?

Un passage qui a marqué pour toujours le retrait du noir et du blanc Qui a inscrit la figure humaine.

Là où avant elle continuait d’alterner.

Que va faire cet artiste dont l’œuvre ne se laisse enfermer ni dans un syncrétisme culturel, ni dans une simple absorption européenne ?

Car le mystère de sa peinture continue d’opérer…

Justement, l’avenir, pour Xie Lei, s’annonce lumineux. Quatre expositions monographiques sont prévues, dont celle de réouverture du LAM à Lille en 2027 – suivi d’une exposition à la Green Art Family Foundation de Dallas.

Une exposition personnelle à Passerelle, à Brest. Une exposition au musée Denys-Puech de Rodez.

Un retour marquant en Chine au Song Art Museum en 2026. À cela s’ajoute une densification du regard critique sur son travail avec des textes de Martin Bethenod, Florian Gaité, Claire Staebler, et un entretien avec Neil MacGregor.

Et sur le plan du marché, une consolidation à l’international avec son entrée dans la galerie François Ghebaly à Los Angeles (cela s’ajoute à sa présence actuelle dans avec la Galerie Semiose, Sies + Höke, Meessen de Clercq).

Le futur de Xie Lei, comme sa peinture, avance par surgissements, par éclats, par intuitions visuelles.

Un avenir qui s’annonce, lui aussi, comme une suite de lumières, de lumière silencieuse !

(c) Julia Marchand, octobre 2025.

Avec le soutien de la galerie Semiose

ENGLISH VERSION:

It’s a great honor for me to present Xie Lei’s work to you today.

It’s both an honor and an important mission.

For those of you who have met the artist, you’ve very probably noticed

his presence,

his respect,

his silence.

Xie Lei is a man of few words. And like all men of few words, he loves language.

A word is never chosen by chance.

There’s something powerful in his relationship with language, in the intensity he gives to each word.

In the potency he gives to each title.

For example, here with his series Fall.

This is an initial external text. The visible part of silence.

This is why I asked myself the question: what internal texts motivate this man?

Who are the children of the silence of his painting process?

I propose that we begin with the series you have immersed yourself in.

Fall is an installation especially conceived for the spaces of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris on the occasion of the Marcel Duchamp prize.

Seven large-format works, measuring 270 x 205 cm, tailor-made for the spaces, allowing the viewer to discover his oeuvre in its full panoramic scale and appreciate his sense of installation.

An environment of blue-green foam, with touches of white, hues from which bodies emerge, one single body, two in the process of falling.

In other words, during an ongoing state of plunging, something that Xie Lei has being seeking to achieve for a considerable period of time.

The choreography of Matisse’s mural La Danse, displayed nearby, might spring to mind. Matisse’s white bodies in motion are echoed by Xie Lei’s opaline figures.

Here, the bodies are all inverted.

They are falling, their heads, napes of the neck and spines are all facing downwards.

So what can we say about the series Fall?

To me, it seems that there are several reasons for a painter like Xie Lei to explore this subject.

The fall is a common theme of many mythologies (Western, Eastern, Chinese).

It is also a major pictorial challenge.

Yet above all the fall is ingrained in each and every one of us.

Gaston Bachelard reminds us that it is in reference to a primitive fear, originating with our tree-dwelling ancestors, who integrated this fear of falling.

In this sense, it is universal, both individual and collective.

It is so deeply rooted… that it has evolved and nestles in other imaginations.

The sheer fall, man’s vertical leap, is rare—even though Xie Lei has sought to express this extreme physical state, as can be seen here.

The fall is the sister of condensation: it gathers within itself other states of being such as levitation, inclination, elevation, suspension and diving.

It recedes into the background behind something else. Art history has shown us this: Yves Klein with his Saut dans le Vide [Leap into the Void] shows us a leap without a fall. He occupies the void, without falling, defying gravity.

The fall brings together other facets of imagination: an embrace, a drama, a romantic tiff.

Faced with this multitude of visions, Xie Lei genuinely asked himself the question:

how can I represent these falls in all their multiple meanings?

By working with chromatic layers, these shades of green and blue, Xie Lei discovered the pictorial equivalent of the polysemy of this state: an almost monochromic environment that tends towards a blurred, plural almost soothing sensation, achieved by applying a series of colors that blend into these moving backgrounds.

Xie Lei applies very delicate, fluid, transparent layers of oil paint to a gesso surface that acts almost like a second skin.

This technique of layering never produces a texture that appears particularly thick. His brushes—broad, made of hog hair—are impregnated with just the right amount of oil paint; exactly like the way he employs words.

The restrained yet intense palette thus produced, give an impression of deep water or the depths of night, where certain places or zones are more saturated and mysterious.

The green takes on a deep hue, almost as dark as black.

Uneasy as black, and yet black itself is absent from the artist’s palette.

We get the impression of water opening onto other material forces:

the impression of water meeting with wind—speed—the impression of water merging with air.

You have perhaps noticed the pearling that surrounds the bodies moving in the depths.

A shimmering of light, a bubbling obtained by the removal of matter.

When the painting reaches its final stages, Xie Lei takes a larger brush that he dips in turpentine, which he then projects onto certain areas of the canvas.

This is not a further layer, it’s a projection: a projection of non-matter, which he will then delicately remove with a soft-bristled brush, paper or his own fingers.

Far from this point onwards, it is a matter of removing rather than adding material.

And of all the gestures that make up the paintings, these are perhaps the most discreet.

They are the ones that give the impression of stars immersed in what feels like water.

They contribute to the texture of the fantasy and the depth of the strangeness that inhabit Xie Lie’s paintings.

How far back can I / we trace the strangeness and dream-like qualities, as aesthetic categories—yet not only those—in the genesis of his work?

In the case of this artist, who was trained to paint from the age of six in China, the exploration of a polychromatic, dreamlike world did not reveal itself directly upon his arrival in Europe.

It has been evolving inside him for a long time. For this artist, who received scholarly training, influenced by both European and Chinese academic traditions, the strange is a pictorial given and an integral component of life.

Even as a child in Huainan, he observed the will-o’-the wisps, the result of chemical reactions, emanating from the graves in the local cemetery.

He observed the depths of water, one of his earliest fears that provided him with his first colors.

This blends in with his apprenticeship, when he learned about mountains and water (shan shui); landscape painting employing particular gestures, in black and white, also including greens and blues, and silence.

This precision technique was consolidated during his years at the Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he enrolled in 2006 on his arrival in France, and in the writing of his doctoral thesis, completed in 2016, on the poeticness of the strange.

It revealed itself, like an epiphany, as he meandered through the museums of Düsseldorf, New York and Madrid, seeking out the polychromatic power of the works of Zurbarán and Velázquez—reproductions of which he always carried with him whilst a student in China.

He also sought out the works of Alonso Cano and Luis de Morales, whom he discovered during his residency at the Villa Velázquez at the French Academy in Madrid.

It was there that he discovered and retained a sort of “color tenebrism” that has found its zenith in Slumbers, a series that deals with an on-going state.

Xie Lei seeks to depict the unfolding moment of an action in progress.

A suspended action whose outcome remains unknown.

Although he has been painting for nearly forty years, cinema provided a formative starting point.

He has already stated that he “tries to make films with his painting.”

In fact, he has been seeking to create a cinematic effect in his art for almost twenty years; more than twenty years ago he was tempted by the choice of a career in cinema.

More than twenty years ago, cinema entered his life through Un Chant d’Amour by Jean Genet, which he watched in an internet café in Beijing when he was still a young man.

And Pier Paulo Pasolini, more specifically Salò or the 120 Days of Sodom, which he particularly admires for its quasi-liturgical, detached methodology and its aesthetic power inspired by classical painting. Then there are silent, visual films like those of Béla Tarr.

Black and white films for an artist who has always rejected these colors.

And there is also Spring in a Small Town directed by Mu Fei.

I would also like to add Apichatpong Weerasethakul for his distended moments, perhaps those of sleep, which open up to other presences… ghostly, vegetal…

And even if cinema is a realm of time, action and narration, Xie Lei insists that he does not seek to tell stories.

What he proposes is a suspended situation.

A state frozen in its slow transformation. As with Slumbers, where he stages almost invisible actions.

Miniscule transitions, where breathing becomes hoarse, while pleasure fades into sleep.

Slumbers reveals a man who is “sleeping, dying or orgasming.”

And for good reason, Xie Lei uses broad, sweeping strokes to create a disturbing blur.

Layers of oil paint produce a dense, tempestuous material from which an uncertain form emerges.

The indistinct face shifts in the background. It is as much a face as it is a shadow: a colored shadow.

Warm, earthy tones: browns, ochres and reds.

Cool tones, principally deep blues and always those greens and blues, verging on black.

Tenebrism in the service of color.

Xie Lei never paints a frozen action but rather one “in the process of happening,” like the present continuous (ing) in English.

The title however is not Sleeping—which would have been too strong, too verbose, too narrative.

Slumbers suggests an inner silence, the vibration of a groaning sound. Its inner text has the profundity of a fundamental human experience.

Of which the very exercise of seeking out “the meaning for me,” or in other words the true meaning, requires us to be discreet observers, surreptitious witnesses.

Xie Lei treats the painting like a frame.

We are looking through a keyhole: 27 x 35 cm, 33 x 41 cm and 30 x 40 cm.

These are the three formats accorded to the Slumbers series, giving it a particular intensity and opening out…

into the polychromy of an inner world.

Beyond time and beyond the principle of framing, Xie Lei incorporates digital light into the secrecy of the creation of his work.

Cinema and painting, as allied peers, serve an oeuvre that calls on its own transcendence to gently transport us towards the idea of a light box as in the Fall series.

Xie Lei creates this light. He shapes it so it illuminates the painting, like a kind of incandescence, a thermal capture or a spectral halo.

This is not the result of applying the color white.

White has been missing from his palette for several years, in the same way as black.

Yet this white is present; he doesn’t paint it, he makes it emerge.

He makes it emerge through transparency, revealing the whiteness of the gesso, revealing its light, or by rubbing away, with a cloth, with a brush or sometimes with his bare hands, the upper layers that constitute the monochrome.

In fact, the figure is more or less a reserve.

A gap.

It isn’t painted, it’s excavated. And this “almost white” is not a color, but a fashioned absence, which flickers a little more in certain places.

“Leaving white,” in Chinese, liú bái, refers to the act of leaving an empty space, an intentional void. I still see that silence.

For Xie Lei, this white is a presence, like the sound effects in a film.

It is a process similar to that of beading.

Excavating the material—which is smooth like skin.

But more than anything else, smooth like an image, smooth like a screen.

Xie Lei treasures oil painting for the effect of a caress it provides.

He can touch it, as it is at once oily, smooth and can be erased.

It’s like cream, he says.

It seems to me there is an echo here, between his way of painting and the caress that erases a subject:

In Fall, a transparent hand appears on the body of a figure.

It touches without grabbing hold.

It is a spectral caress, the touch of a spectre.

In this sense, painting is an apparition.

The image should be considered as part of an editing process, which once again belongs to the world of cinema.

It might be considered as a haunted space.

If we press forward with this reading, can we still discuss the idea of series in Xie Lei’s work?

That have a beginning and an end?

His work is based on overflow, eruption and reappearance.

It is based around recurring motifs, leitmotifs that are revitalized from one canvas to the next.

The paintings are never quite concluded but always open to the future as well as the past.

As at the BnF [French National Library] in the Apocalypse exhibition, where Xie Lei’s work is linked to history in a seamless process that brings one era closer to another, one work closer to another: since then, Xie Lei has presented open, unstructured sequences.

In this sense, Fall is not just a fleeting instant in the exhibition: it is a leitmotif, an obsessional figure that will reappear in other works to come.

If we continue with this interpretation, these paintings could be seen as panoramic representations of human states—a man being caught in both the acts of sleeping and falling.

Perhaps there are even two representations of this man;

one vertical

and the other horizontal.

One who is sleeping

and one who is falling.

Even if the fall is already taking place, perhaps while sleeping in Slumbers, since according to Jean Luc Nancy, “sleep is the setting for all falls, it sums them up.”

Thus, two figures could well form a single one.

Two states of the same body.

Where can Xie Lei be found in his paintings?

And where does he choose not to appear?

Xie Lei does not omit himself as a body in his painting.

The size of the body could well be his own—a life-sized body.

Yet the canvas is not a self-portrait.

It might rather be considered as the setting for a shifting self, escaping from any kind of identity attribution.

This is what José Esteban Muñoz refers to as disidentification: a flexible manoeuvre between withdrawal and appearance, where identity becomes both evasive and evanescent.

Xie Lei asserts his presence in his painting through its absence, through his elusiveness in his blurred lines, in those he erases with his own hands, leaving here and there the discreet imprint of his fingers.

Through this erasure, he inscribes his own presence.

And perhaps we should interpret these figures—asleep, falling or floating—in the light of this notion.

Their blurred outlines echo with the erasure of identity; the way they float suggest a kind of decentring of the self.

Where the artist silently deals with who he is: painter, man and expatriate.

He has no desire to shine a light on these traits.

He prefers to dilute them in the generous space afforded by disidentification.

He deals with them inside himself: they are his inner text.

He choreographs an absence of self to open the way to others: viewers can identify with these nameless, anonymous bodies, which show no clear distinction between male and female, even if the male gender is sometimes suggested in some of the Fall or Slumbers’ paintings.

Overall however, they convey the image of universal porous bodies, into which anyone can project their own vulnerabilities.

We can also identify ourselves in the white spaces, which are never empty: they crackle with meaning.

Or even in the shadows, which according to Annie Lebrun, enable us to flourish.

These colourful shadows, which take the form of mysterious spaces of lyrical rebellion, all uttered in whispers.

What he is trying to achieve is the recognition of a common, underlying foundation, a shared memory (returning to the fall as a primordial, common fear?). Xie Lei is truly a formidable unifier.

His work also displays signs of reality.

He withdraws this self into the background to reveal bodies and subjects that have a slightly more direct relationship with reality.

As is the case with Absorb, which is shot through with powerful images that current events in the world reflect.

Or in Au-delà, inspired by an image I prefer not to mention.

One would betray the silence of his work by seeking to make great speeches about it.

Xie Lei never overstates but rather opens and offers us the means to confront an inner panorama by plunging ourselves into the sensation of water, into falling, sleeping or into the colors of his shifting backgrounds.

And the question I now pose to myself is:

doesn’t this panoramic perspective of his oeuvre ultimately nourish this ambition?

That of inviting us to plunge into our own inner beings: a romanticism of disidentification.

What will this painter do, who at the age of 15 left his provincial home of Anhui to study in Beijing, at the high school affiliated with the Central Academy of Fine Arts?

Who subsequently travelled across the world, driven by an innate desire, in order to continue his education at the Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he has lived and worked since 2006.

More specifically in his studio in Thiais in the Parisian suburbs, close to a garden where he draws some of his plant motifs, such as magnolia leaves.

What will this painter do, who was not content with painting as just an activity, but thought deeply about it, formulated it and questioned it? Because he feels endowed with this responsibility.

He was the very first artist to pursue a SACRe [Science, Arts, Creation and Research] doctorate at the Beaux-Arts and the École Normale Supérieure.

What will this painter do, who dreamed of France while in China, then dreamed of Italy and Spain when in France?

Who learned something of Italy through his residence at the Villa Medici in 2024.

Who went to see Velázquez’s work in New York, that of Titian in Vienna and that of Zurbarán in Düsseldorf.

Who experienced a revelation while visiting Madrid during his residence at the Casa de Velázquez—part of the French Academy—in 2020, during a moment “out of time.”

A passage that marked the withdrawal of black and white from his palette forever.

Who placed the human figure there, where before it had continued to alternate.

What will this artist do, whose oeuvre cannot be restricted to cultural syncretism or a form of absorption of European art? For the mystery of his painting continues to weave its spell…

Indeed, the future looks very bright for Xie Lei.

Four solo shows are already scheduled, including the reopening of the LAM [Lille Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art] in 2027, an exhibition at the Green Art Family Foundation in Dallas, a solo show at the Passerelle in Brest, an exhibition at the Denys-Puech Museum in Rodez and a landmark return to China at the Song Art Museum in 2026.

In addition to these exhibitions, he is enjoying an increased critical examination of his oeuvre, including two books published by Semiose Editions, with texts by Martin Bethenod, Florian Gaité, Claire Staebler and an interview with Neil MacGregor.

And in commercial terms, he has consolidated his international presence with his acceptance into the François Ghebaly Gallery in Los Angeles (in addition to his current presence in the Meessen Gallery in Brussels and Sies + Höke Gallery in Düsseldorf) and in numerous public collections.

In the image of his paintings, Xie Lei’s future is advancing in surges, flashes and through visual intuition.

A future which also promises a succession of illuminations… of silent illuminations.

(c) Julia Marchand, October 2025, with the support of Semiose